A Trinity that Matters

Or "What the anthropology of Islam taught me about Trinity Sunday"

One of the side benefits of my relationship with my wife, a professor of Islamic studies and Southeast Asian studies, is that from accompanying her on research trips, going to many of her talks, and reading and offering the occasional suggestion on drafts of her work, I feel like I have gotten to know the scholarly literature in her fields pretty well despite having read almost none of it. Thus I, like Verena, am a fan of the anthropologist Amira Mittermeier and her work on the unseen, “imaginal” world among Egyptian Muslims during and since the Arab Spring. The mere title of her first book, Dreams that Matter, is worth the price of the volume. She’s an anthropologist, but she is part of a movement that takes unseen things as agents among the people she studies, thus accepting her informants’ insistence that their dreams come from elsewhere and have something of a life of their own. Like I said, I haven’t actually read this book, so that’s probably not an adequate description. But I was curious enough about a reference in Verena’s book manuscript that I followed it up: Prof. Mittermeier is working an ethnography of God (this article is open access).

Decentering the human and political

This does not mean that she believes in God or doesn’t (I have no idea), but given how central God is in the world of her conversation partners, she wants to make room for God in anthropological writing, “decentering the human,” and moving (as per the title of the lecture) “beyond the human horizon.” I must admit, it was a surprise for me as a priest and a theologian who might describe everything I do as “making space for God” or “centering God” (and who, just in case this wasn’t clear, does believe in God) to hear this language used in the context of anthropology of religion. The writing Mittermeier proposes is not conceived of as an act of devotion to God, but she wants to make space for God (as in her earlier writing, for dreams, and in some other recent anthropology for spirits, forests, and even mushrooms) as something unknowable and uncontrollable that cannot packaged into the dominant western epistemological norms (of which she admits that she is, somewhat ironically, a keeper as an academic). As a note in passing that I will develop more fully some other time: academic theologians (of any ecclesial or ideological alignment, but especially more confessional) are rarely willing to do this in their writing. No article in systematic theology I can think of off the top of my head has taught me to think about openness to God, allowing “things” to have an agency of their own, and living with incommensurate epistemologies, than this article by Verena (also open access, as her book sometime next year will be. A version of this article will be a chapter).

Mittermeier’s article was originally given as a keynote lecture at conference on the theme “From Ethics to Politics.” Theologians are often given to the same impulse as anthropologists. Whether we are working out our own articulations of the divine and the practices whereby we engage it, or reporting and theorizing those of others, we tend to want to show that these articulations and practices matter. They make a difference politically. This is of course in the larger sense of the word “political,” which is not limited to parties, elections, or government institutions of any country. It means something more along the lines of how human beings share and contest power, distribute resources, and engage in and regulate collective life. When we or the people we study do not seem to be directly engaging these things, we often talk about how they form a certain sort of “subject,” or perhaps “habitus.” But Mittermeier allows the people she studies to be the experts, and notes that they tend to react strongly against the characterization of their activities as political. (This builds on earlier work by the late and much lamented Saba Mahmoud, also in Egypt, which showed in a book called Politics of Piety that the practices of Egyptian women cannot always be reduced to resistance or compliance).

Noting that “the figure of the ‘human’—and related concepts such as human rights, humanism, and humanitarianism—have not necessarily brought about more justice in the world,” Mittermier sees her call to decenter the human and make space for God in ethnography as “not [to write] out questions of class, race, or gender, but “there is a difference between paying attention to economic and political contexts and reducing God to these contexts.” What matters in anyone’s life and any religious tradition (I think, and I believe this is what Mittermeier is saying) might be more than what matters practically and politically for human beings. As a Christian, I would add that those of us who believe human beings are created “in the image and likeness” of an incomprehensible God cannot claim to know what a human being is in any stably definable way, and thus should have some humility when we say what matters for us and others. The fact that the church of the colonizers failed and fails to do this is one of our most grievous faults.

The Usefulness of the Trinity (or not)

It is with these lessons of Mittermeier’s work in mind that I think about the Trinity as we approach Trinity Sunday (June 15 this year), which my church regards as one of the seven principal feasts of the Christian year. Christians, particularly of a progressive, liberal, or social justice-seeking orientation, want our doctrines and practices to matter politically. We are not wrong to do so, and I think we feel a particular responsibility because of our traditions’ complicity (if not outright initiative) in so many of the political evils that trouble the world. Sure, we like to say that the violence of the 16th and 17th century religious wars in Europe and the European projects of colonization and enslavement were not primarily or at least not only about Christianity, but about emergent nationalism, capitalism, and even secularism. We have a point, and “religion” certainly functions as a scapegoat or boogeyman in much white Euro-American secular discourse that remains quite comfortable with the neo-colonial world order. But it’s pointless and even something of a tasteless joke to deny that the symbols, doctrines, stories, and institutions we love posed little practical impediment to colonizers and slavers, but quite easily lent themselves to the imaginaries of the participants in those projects as they made sense of their actions. They benefited materially from those actions, and were often enough active participants, as many still are. As Willie James Jennings has put it, Christianity is operating with a diseased social imagination. And we want to show that our tradition, which bears a large part of the responsibility for the problems, has at least the potential to solve them.

The Trinity does not find an easy place in this sort of articulation of the aspirations of Christians. When I was a graduate student in ministry (a Methodist at that time, in a historically Baptist Divinity School, hanging out with a lot of Disciples of Christ), I remember well that I had the sense that the Trinity was important, but more than once met questions (good ones) from my peers in less dogmatic or confessional churches about why I would want to hang on to a speculative doctrine that was at least not obvious in the Bible, seemed to introduce hierarchy into God, and all this for no practical or political benefit. I wrote my masters thesis as a way of struggling with that very question, and under the tacit influence of social trinitarians like Catherine LaCugna and Leonardo Boff (I had not read much of Miroslav Volf [alas, not open access] or Jürgan Moltmann on the topic yet). I based my thoughts on what was probably a misreading of Augustine (De trinitate VIII), though I think I might be able to salvage it if I ever have the time and the wherewithal. With unending gratitude to her generosity to other approaches, Kathryn Tanner liked it well enough to take me on as her PhD student, and it was through her work that I became convinced of the flaws of social trinitarianism (she left for Yale shortly afterward, but remains one of my main influences).

There are all sorts of problems with the idea that the equality and relationality of the Divine Persons provides an ethical norm for human relations characterized by both equality and difference. As Tanner says, we just do not mutually coinhere in one another the way the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit do. And at any rate, the doctrine doesn’t seem to teach us much that we didn’t already know. Furthermore, Linn Tonstad has pointed out, it is easy enough to take away very differnet lessons from the Trinity than those of us who emphasize equality want to find there. Many have. Tonstad applies her critique to all sorts of other retrievals of the doctrine of the Trinity, including one that I actually quite like and that is very popular in my church circles, that of Sarah Coakley (there used to be a few non-paywalled versions of the first chapter on the internets, but I can’t find one now). Coakley taught me that when it is based on a practice of contemplative prayer, trinitarian reflection destablizes hierarchical and binary constructions of gender. I’ll come back to this because at the end of the day, I agree. But Tonstad rightly points out that anytime we invoke the equality of substance of the Divine Persons to say that apparent hierarchies have no legitimacy, someone else could just as easily say that the relations of origin and submission among the co-equal Father, Son, and Holy Spirit demonstrate that hieracrhy and equality are perfectly compatible, and that women should submit to men in marriage and the church as an expression of their equality in difference.

If you still with me after that little lit review (this is what happens when you never quite accept that you’re not an academic anymore), my point in all this is that even though many of us want to articulate the Trinity and other doctrines in a way that show how practical and liberating they are—how politically effective—no way of doing this has solved the problem of irrelevance without introducing other problems. We could leave technical doctrinal formulations aside and say that devotion to the Trinity is important because it forms Christians as a certain sort of “subject”—I would ultimately say this—but even here, one has to point out that we are not the most impressive set of “subjects.” Ghandi supposedly remarked that after he first read the Gospels, he was so impressed by the teachings of Jesus that he would have become a Christian, if only he’d never met one!1 The political efficacy of the Trinity—at least any liberating sort of political efficacy—is not all that aparent on either theoretical or practical grounds.

Resisting Classification

But go with back to Mittermeier for a second. Are we sure that the only way something is worthy of our attention and analysis is if it is of political utility? Or indeed, of any practical utility to human beings as we presently experience ourselves? So you can use the logic of the Trinity for liberation or oppresion. Part of me wants to say “big deal.” In this respect, it is no different from absolutely any other thought, idea, or symbol. If you read the essay I linked to, you’ll see that this is also the case with the Islamic “Allahu akbar.” It’s the case with supposedly emancipatory ideals of autonomy, freedom, secular government, or on the other hand, collectivism, communal ownership of resources, and government by the workers who produce wealth.

But this deserves more than a dismissive chortle. Perhaps like the radical monotheist confession of “Allahu akbar,” the Christian confession of God as Three and One simply cannot be classified as political or apolitical, practacal or impractical, even liberative or servile. Don’t get me wrong: it is the calling of Chistians as follewers of Jesus to pursue liberation and justice in whatever way we possibly can. You don’t need a doctrine to convince you of that (or: none likely will convince you if you’re not convinced already. And let’s face it: plenty seem not to be). We are obligated in this life to seek the reign of God and God’s justice (Matthew 6:33—pretty much everytime you see the word “righteousness” in the English New Testament, you could also translate the Greek word as “justice,” and vice versa). Or in the words of the great song by the Black American composer Bernice Johnson Reagon, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.” God is not going to let you off the hook for any trace of quietism (or worse, dominionism), so save that for the confessional. But remember that call for humility? We are too deeply formed by the very structures we would resit to be able to imagine what a world without them would look like yet. We have to try what we can, but our present ability to classify something as politically conducive or not-conducive to our political program cannot be the only measure of what matters, anymore than any other human horizon.

Still, as a friend remarked to me at that time in my life when I was first enfatuated with and then put off by the Trinity as a patern for human relationality (it was either Linn Tonstad or Daniel Shultz), Moltmann and those who followed his lead may have been wrong, but they were wrong for all the right reasons. The social trinity may have become unfashionable and may in fact be a flawed idea, but I think any theobro who sneers at the mention of LaCugna or Boff will benefit more from your prayers than your desire for approval from the Serious Theologians.

Wrong for the Right Reasons

The “right reason” is that even if we absolutely must not make our political or even human horizons into the only measure of what matters, we do know that God is a God of liberation. We have experienced God as such. We all have our testimonies (that we may be afraid, or just too polite, to include in theological writing) of how God has shown Godself to us as a God of love. We know ourselves and the world to be loved by a powerful God who desires the just and equitable flourishing of all creation, human and more-than-human. I have mentioned here but not dwelt on my own coming to terms with the sexual abuse I experienced (in a church context); what I have not named here explicity is the way that God called me into healing specifically through meditation on the Trinity as the eternal love of God that would overcome and heal my experience of myself that had been distorted by the abuse. That was at the same time as I was working on that thesis, and that part I stand by.

I also stand by Coakley’s insistence that it is our communion with the Triune God which will undo the hierarchical and binary constructions of gender we just can’t shake, and which seem natural (and race, and all the others). As a Christian, what else should I set my hope on? I just have more modest hopes for what the expression of this reality in systematic theology can do than some of Coakley’s more enthusiastic statements (which are nuanced elsewhere). I know (and regret) that the devotions of my church and others do not necesarrily lead straight to a liberative politcal power; there is no way you can express the mysteries in human language and symbols that can infallibly enusre that you are being formed only in the right way by them, and not in ways that further internalize and reinforce hierarchies. Then again, what are the wrong ways, if not right ways taken at the wrong time? (As another Chicago friend, Ian Gerdon, once said to me, what is an idol except an icon used incorrectly?) Even our right subjectivities, liberating politics, and sound understandings of divine and creaturely truth are only partial, and will grow, and we will learn to inhabit other insights that now seem contradictory. “For now we know in a mirror, dimly.”

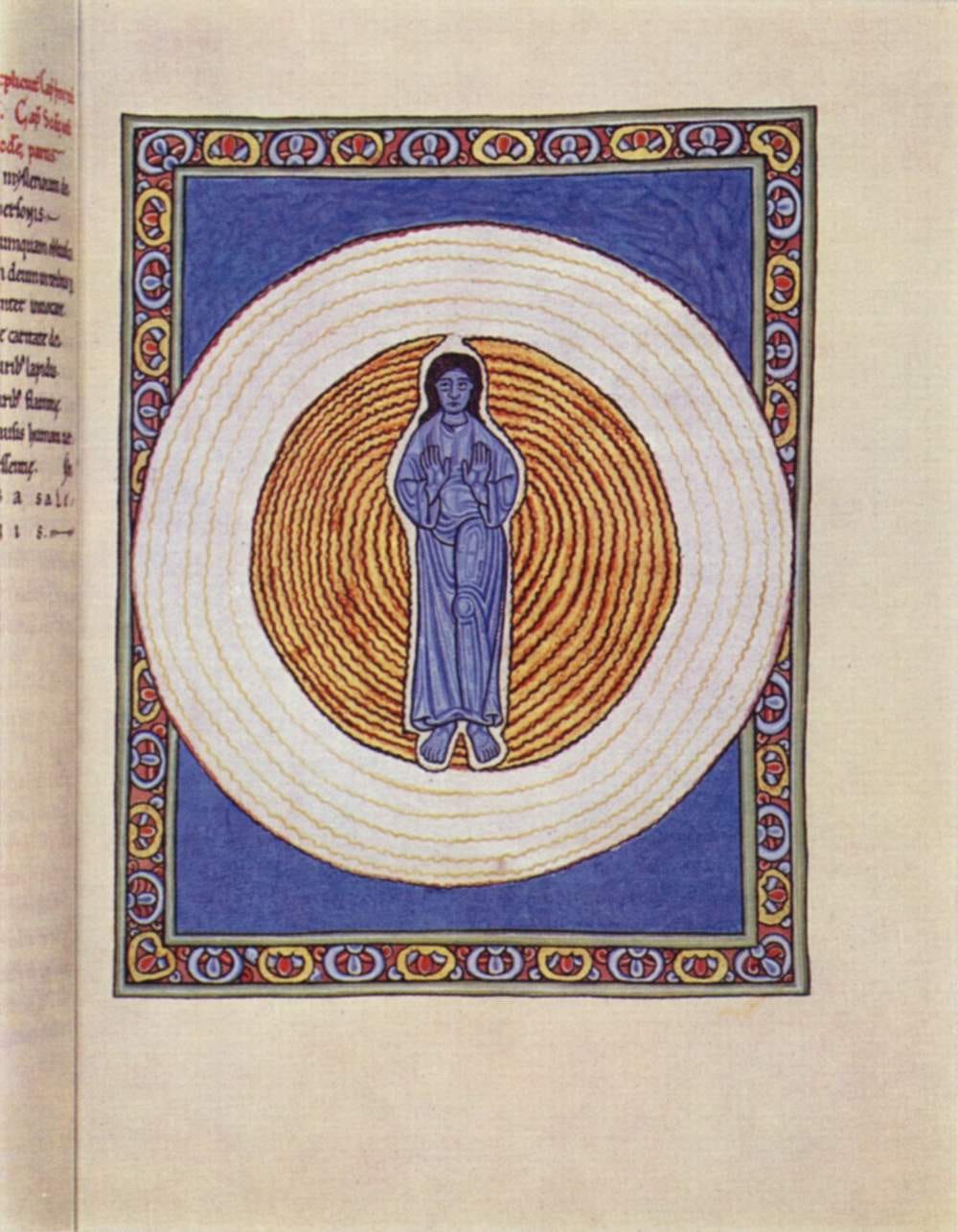

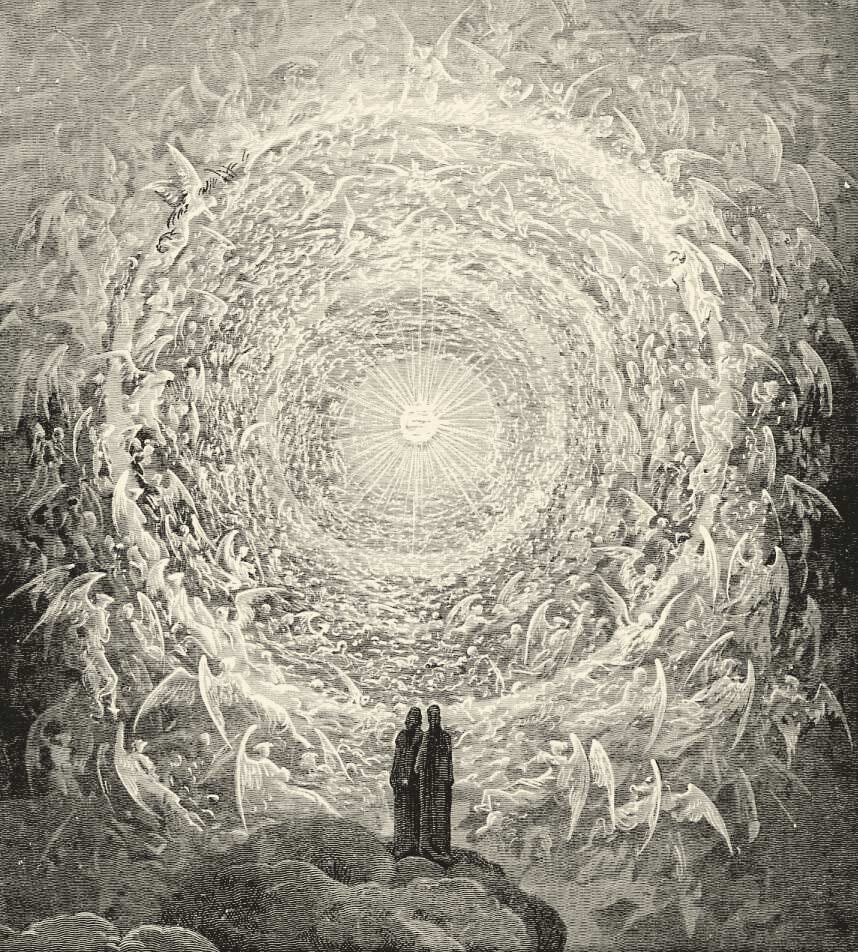

I will write on some other occasion about how the Trinity is the Christian way of affirming the absolute distinction between God and not-God, while also believing that not-God is being joined to God (deified, we now like to say). I have read the Fathers and Mothers much more closely now than when I was 24, and I believe that the doctrine of the Trinity does in fact grow from their emerging understanding of redmeption, and plays an important role in how God prepares us to receive the gift of Godself. But this is already longer than it should be, and I won’t have time to trim it much if I also want it posted before Trinity Sunday.2

So for now, let me leave you with the suggestion that when you are invited to confess and meditate on the Trinity, this Sunday or any Sunday, let it be there as the uncontainable and uncontrolable, only partly knowable Love: passing thought and fantasy. Apparently even anthropologists are writing in ways that seek not to circumscribe God to our own canons of inteligibility and usefulness. How much more should worshipping Christians welcome God into their preaching and prayer as that which they only partially understand?

There is no point in taking offense at this. We rarely say the Nicene Creed without also confessing our sins in the same liturgy (this is why I like the less common version of the Episcopal Eucharist that puts the confession of sin up front, long before the Creed). Our appeal to God for acceptance and to the world for the credibility of the Gospel is just the grace of God and the blood of Jesus, not ourselves as impressive recipients of it. “We do not presume to come to this thy table, O Merciful Lord, trusting in our own righteousness, but in thy manifold and great mercies,” etc.

Don’t worry; we’ll do Trinity Sunday again next year.