I have gotten a few requests to make this sermon available. I don’t normally do sermons here, but as this is preached in the wake of some healthy coming-of-age conflict in a new church, I think it qualified as “things I have learned as a church planter. So here it is, recorded and as a manuscript. The propers are Easter 7/C, with John 17:20-26 as the Gospel reading.

If you walk into a family’s house, what pictures are you likely to see? Verena’s parents have a bunch of black and white photographs of dignified, if a bit stern looking ancestor. Those pictures weren’t so easy to take back then, so people got dressed up for them and assumed these rather serious poses that we now see as a bit ridiculous. Verena and I have a picture of the two of us looking much more relaxed. We’re standing in front of a reservoir in an otherwise arid landscape in Morocco, wearing outdoor clothing, looking happy if a bit sweaty, after a day of more-or-less hitchhiking to see the sites around Ouarzazate and Skoura. I have to say that we look pretty cool. If you go to Mpho and Marceline’s house, you’ll see a smiling Mpho standing between Archbishop Tutu and President Mandela. She looks pretty cool (granted, she actually is). In many households, graduations feature prominently. Weddings even more so.

And why not? You wouldn’t be wrong to be a bit cynical and say that the wall of photographs is a performance of ourselves at our best, often our imagined or staged best, a pretense to impress a visitor and make them feel like they’ve walked into a house inhabited by Very Together People who have totally figured out this life business. And we might take a bit of a guilty pleasure if we make them at least subconsciously assume that these pictures must be typical scenes of life in that family. But that’s probably not all it is. Nothing is ever just any one thing. These moments of joy and triumph may not be typical, but they’re real, and the remembrance of them is an offering to our future selves, our visitors, even to God. Heck, I’ll even go so far as to say that this is true even if the photograph is rather highly staged and the joy or triumph of the occasion is largely retrospective, or let’s say aspirational. Or if damn, that was actually a crap day, but we look pretty good. And then even if that vacation or that award ceremony isn’t in the least bit typical and the smile on your face in the picture masks the excruciating pain you were in at the end of that marathon and you actually spent the week afterward unable to walk, your pictures—or other ways of remembering—might invite the visitor and also your future self into the joy you are trying to build. It’s not inauthentic. Or at least not entirely inauthentic, or need not be.

Now if you walk into a church that is more normal than ours, or go to its website, you’re likely to see a fairly similar set of pictures. And old parish of mine used this photo that showed our church filled to the brim with very diverse looking people, with the bishop and a bunch of other people laying hands on a woman. It looks like an intense but loving and joyful prayer for healing. It’s such a great picture that the diocese actually started using it on their website. There was no need to point out that it was from several years previously, taken at a special event, and most people would have had to scratch their heads to remember another time in the last decade when the church was that full. And I loved that picture and my people loved it, because it showed who were and what God did among us, a people of energy, joyful worship, and actually not-infrequent extraordinary healing. And it was an honest-to-God diverse community!

But while all these webpage photos may be perfectly authentic, if probably never typical, what a contrast they make with the central image in almost all of these churches, which is usually a cross, often with the figure of the Crucified One on it. There have been eras when the crucifixion was a less prominent symbol. The Resurrection was sometimes more prominent, or scenes from the lives of the church’s people. It was in the 12th century, in western Europe, when the crucifixion really started becoming the central symbol. But even if medieval crucifixion piety is sometimes over the top, it’s onto something. All four Gospels are basically Passion icons in written form.1 Like Paul’s letters, they proclaim the Resurrection, but none dwell on it. Christ Crucified is the image that stands in for the whole.

We find ourselves in that week between Ascension, last Thursday, and Pentecost next Sunday. It’s still part of the Easter season, when we remember, meditate on, and dwell in the power of the Resurrection. And that is why we are ever here. Without the Resurrection, the life of Jesus would be a pretty depressing story, and we have enough of those already. But have you noticed that the Gospel stories we have read together since Easter mostly haven’t been from the 40 days that Jesus spent with his disciples after his Resurrection? That’s because there aren’t many. Matthew has two resurrection appearances of Jesus, Luke and John have maybe four, and Mark doesn’t have any. It’s what gives the story any meaning at all, but it occurs offstage.

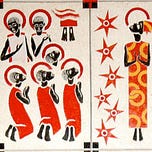

And even in the Gospels where Jesus does appear, the frequent image of him is him vanishing as he blesses them. This happens a couple of times, most prominently in the Ascension. I love the picture of the Senegalese church mural that I found for this week’s newsletter. It shows the apostles and the Blessed Virgin Mary, but the only sign of Jesus is two feet at the top of the painting, on his way to the sky. And it’s always just them, the disciples in these stories and pictures.

The Crucifixion remains the last public image of Jesus: that image of everything gone wrong: of pointless pain, of betrayal by his own community and his own friend, abandonment by his followers, maybe even by God. Not the joy and triumph of God’s justice and God’s reign, but the complete and utter failure of even the Messiah to bring it about. What a moment for a selfie! But that’s what’s on the altar, or over it. We’ve become used to it, so the shock is blunted for us. And of course, it’s been abused and appropriated, like everything else, and those who exalt the Crucified One as King have often enough told the truth the way Pilate and his soldiers did, hailing him as they strike him; hailing him as the strike others; calling him Lord while they enthrone Spain, the Netherlands, whiteness, global capitalism. The way of all things has been perverted, but still belongs to God. And the horror of the cross is God’s solidarity; the failure is God’s victory. And that image of the Crucified Savior at which the devils tremble is what is given to the world, to cringe at or to embrace, or both at once. And so we lift it up in one way or another even in the season of the Resurrection, just as we proclaimed the Resurrection in Lent. The victory of God is in the failure of the cross, or—another manifestation of the same thing—the fullness of God is in broken bread.

Or yet another manifestation of the same thing: us. Yes, us. This is the mystery of Jesus’ high priestly prayer which concludes in today’s Gospel reading: “As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me. The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me.” This is the prayer of Jesus right before his arrest, speedy show trial, and crucifixion. Embracing the coming horror, he names it as the consummation of everything he has been doing: offering the whole of his own creation in which he has been living back to God, and joining a human community, with a special role in that offering, to himself. And he joins us so closely to himself that when the world sees our life together—or when we do—it sees the life of the Triune God. It perceives the earthly manifestation of God’s eternal life of communication with God—because we are odd monotheists, for whom the divine Oneness is also a plurality, Three Divine somethings who each give to the others everything they are. There is both oneness and multiplicity, real difference and equality. No, you can’t understand it and neither do I. The contemplation of the Holy Trinity is for the end of the journey of our lives, and even then it will never be exhausted. And in another sense, it’s presented to us all the time, and through us, to the world, in our very own life together. We too have been made one. Our oneness is not the oneness of God, nor is our plurality the plurality of God. It’s the part that is visible, the life of Jesus to whom we we are joined, whose life is always lived in perfect relation the Father and the Holy Spirit, thus manifesting the whole Godhead.2

To see and participate in the life of those people who are left watching as Jesus’ feet disappear into the sky, is to see and participate in his life, and thus in the life of God. It is this by which the world will believe that the Father sent him. Us. Which is good news… sort of… This is why the earliest church did not focus on the cross as prominently as some later ages, because the life of the church displays the same reality. And that might seem a bit more appealing to many of us, but remember that the life of the church displays the same reality. Which means it includes the miracles and the wonders that Jesus performed and the pictures of large, diverse groups of smiling people that grace church websites.

But all the signs are leading up to that one sign that can’t be avoided, the cross that is the breakdown, failure, and defeat of all of them, that is somehow God’s victory. And in fact, we’re a mess. “We” meaning the whole church on earth, whatever its institutional manifestation. And “we” meaning, you know, us. All Saints. The ways in which we or any other church is a mess are myriad. And sometimes the ways in which it’s a mess are also part of what makes it cool.

And there are the ways in which we’re a mess that are just a mess. The ways in which that oneness for which Jesus prayed remains more aspirational, or more of an unseen truth. And just as the glorious and beatific life of God must include and overcome the horror of the cross, so in us it must include and overcome the big and small ways in which we do not agree with one another, in which we hurt one another, whether we sin or just communicate badly. The oneness of God that Jesus draws us into, and the love by which they shall know that we are his disciples and that God sent him, must include those tensions, contradictions even, between our partial visions and our limitations in expressing them. And the value of the whole thing is that no matter how wrong someone else might be—or you might be—they have something of the mind of God that you need; you have something of the mind of Christ that they need. You are each something of the cross that the other must bear, and you are each something of the glory that is being revealed in them and in us.

You will miss what is best about any human community and any human life if you start making your way to the door as soon as you realize that the pictures hanging in the hallway aren’t representative of daily life. That the happy couple embracing by the lake shore have as many fights as any other, that the church is full of sinners and idiots, of whom I am the chief. But stick around, and you might find that the reality is even better than the pictures. It is the life of God, after all. And: if you believe in exalting the failure of God as God’s victory over every evil, don’t be afraid to let us and others see those pictures of your own failures. Because we will love them, and love you, and thus will the whole world know the love of God that is in Jesus. May he be praised, worshiped, hallowed, and adored on the throne of his glory in heaven, in the sacrament of his body and blood, and in the lives of his faithful people. Amen.

This was the argument of Margaret Mitchell, which I heard her make on a number of occasions. It can be found in her essay on “The Emergence of the Written Record” in The Cambridge History of Christianity: v. 1: Origins to Constantine (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006). pp. 177-194

I came of age at a moment when social trinitarianism was definitely out, and I am fundamentally influenced by Kathryn Tanner (my sometime advisor) who argues that in Jesus, we can have by grace the relationship to the Father and the Holy Spirit that he has by nature (see the chapter on the Trinity in Christ the Key). But social trinitarianism has had some purchase for people I love and respect, and for whom it has been a way into an otherwise US/European/male-dominated discourse. So I believe it would be wrong to move on from it too fast. I once heard someone (I think Linn Tonstad) say that Moltmann and some of the others were “wrong for all the right reasons.” At any rate, the theologian looks at his own sermon here and regrets that it just wasn’t the time or the place to try to work this out. So for now, no: the Trinity is not the patern for human relationships, but if you argue with me, I’ll prbably just say “yeah, you might be right.”